Open collaborative design

|

Open collaborative design involves applying principles from the remarkable free and open-source software movement that provides a powerful new way to design physical objects, machines and systems. All information involved in creating the object or system is made available on the Internet – such as text, drawings, photographs and 3D computer-aided design (CAD) models – so that other people can freely re-create it, or help contribute to its further evolution. It is essentially the same principle that is used to progress scientific knowledge, however in reality it is much more open and transparent than much of contemporary scientific research.

A core element of this development model is a principle called 'copyleft' Open collaborative design is a nascent field that has huge potential to radically alter the way we create goods, machines and systems – not only for personal items but all the way up to components of national or global infrastructure.

Contents

Open collaborative design, empowered by advanced open-source CAD software, allows anyone — not just designers and engineers — to easily create new designs of products. It provides a vast array of 'copylefted' modules and artefacts for people to make use of in their designs. This not only means that people can customise things for their own needs and tastes, but makes the design process much more efficient and helps avoid the huge duplication of effort that occurs in design and engineering currently. These principles can apply to designing the simplest things that can be made by individuals, solutions for communities in the developing world, all the way up to complex large-scale systems of national or global infrastructure involving thousands of people. Because the designs are not closed or proprietary, people are encouraged to contribute knowing their involvement not only benefits themselves but anyone else might use the results of their efforts. It also means that designs will evolve far faster because of the huge amount of parallel development that is likely to occur. Giving these designs physical form will become fast and easy due to emerging high-speed, flexible manufacturing techniques. As a result the open design ecosystem will effectively become an internet for physical items — and the impact on society is likely to be as great as the web has been with respect to information. Economic realities discourage large corporations from being really innovative. Corporations are unlikely to risk spending money to develop anything for which there is not a proven market. However, enthusiasts and consumer/producers who make things for their own personal use are often highly innovative and willing to make very novel products. Music is a good example of this: corporate-produced pop music is repetitive and without imagination; innovative music only comes from amateurs who are doing it out of passion. Therefore an open collaborative economy allows faster and greater innovation than a profit-driven economy. An open collaborative project is always a work in progress. Wikipedia, for example, is always being expanded, streamlined and improved. With a lot of different people contributing to it, it continually gets better and better in small increments. Multiple versions can be developed in parallel acting like an evolutionary system. Many experimental improvements may not turn out to be better, but those adopted with further iteration develop from promising or successful examples. The community of developers and users act as the selection mechanism. One of the core components necessary for open collaborative design to truly take flight is an advanced free and open-source computer-aided design (CAD) program to allow anyone to easily generate new designs or customise existing ones. The program should include a special browser to enable finding and importing open-source components and machines from the 'universal commons' as well as analytical tools and 'physics engine' The availability of user-friendly open source CAD software will be essential to allow the widest number of people to engage in this creative activity, which should help create a more diverse ecosystem of objects, machines and solutions. There is no reason, with thoughtful implementation, why this software shouldn't be intuitive enough for children to use easily. It could explain mechanical and engineering principles along the way if the user wished, and also be a place to store detailed contextual development notes, wiki style, to help others understand the workings and decisions made. The virtual nature of the designs mean that far-flung people via the internet can easily work together on the same design, either working individually on various sub-assemblies of the whole or collaborating directly on the same part. The restrictions of having to finding people local to yourself with similar interests and desires becomes much less of an issue. At some point virtual designs such as Computer-aided design (CAD) models, need to be turned into physical objects, which unfortunately isn't as straightforward as downloading software from a website. Building, testing and modifying physical designs requires effort, time and material cost, although with access to emerging flexible computer-controlled manufacturing (digital fabrication) this complexity and effort becomes drastically reduced and highly repeatable.

Some of the ways that collaborative designs created on a computer can be physically forged range from getting your hands dirty and crafting it yourself, to sending the design, or at least parts of it, as an electronic file to an increasing number of computer-controlled manufacturing systems such as rapid prototyping or advanced multi-axis CNC machines  So what about free riders? What happens when there are people who only take and never give anything back? Well, nothing really. Contributors are not expecting a specific quid pro quo arrangement — they get plenty in return from using other things in the universal commons. This is the essence of a post-scarcity economy; when a resource is abundant, it can be given away without expecting anything in return. If it is trivial to duplicate the results of someone's efforts then the more people who are able to make use of it, the better. The situation is not zero-sum — people are not going without as a direct result of someone else having it. A situation of abundance currently exists with regard to information on the Internet; it is free to replicate, I can give it to others without going without it myself, and as a result, people give it away freely and take it freely. Consider free and open-source software where anyone with a computer and internet connection can download the Firefox web browser or OpenOffice office software for free. Most people will be consumers rather than contributors, but this is of no consequence. After a while of enjoying the fruits of open-source, many people are only too happy to contribute in some way, giving back to the community that has provided for them. The fact that they are not required to do this, in many instances makes it more likely that people will do so, uncoerced. This is human nature. There are many names that this embryonic movement might go by:

There is no reason why open source development methods currently used with many software projects cannot be applied to machines and systems in the physical world. In fact physical objects are much more intuitive to understand than abstract computer code especially when viewed using 3D CAD that can show grouped sub-assemblies, exploded views, kinematics, cross-sections, supporting animations and notes. It is just that the freely available tools and infrastructure needed for this to be possible do not yet exist in a user-friendly and mature state needed for widespread adoption. All the technologies exist, they just need to be put together in the right way and refined.

The simplest method is to share information through a website on how to make things using text, diagrams and photographs. A more sophisticated way to collaborate on complex machinery and products would be to share CAD assemblies much like project teams do in engineering and product design companies, knitted together with supporting information in an open and freely structured environment, much like a wiki There are certain barriers to overcome for open design when compared to software development where there are mature and widely used tools available, and the duplication and distribution of code cost next to nothing. Creating, testing and modifying physical designs is not quite as straightforward because of the effort and time required to create the physical artifact. However the physical world is catching up fast with the virtual world in this respect. 20th century economics was driven by an assumption that people act exclusively out of self-interest. If you want to make people perform better, so the wisdom goes, you reward them with money and privileges, and if you want them to stop doing something, you threaten them with punishment. This is the almost unquestioned common-sense of the entire economic and corporate landscape, yet it is not well proven. In fact, there is abundant evidence from social and psychological research that this sort of extrinsic motivation These are some reasons why someone might want to contribute to the 'universal commons' of free and open designs:

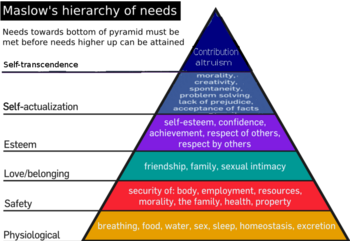

A relevant quote from Benjamin Franklin “... as we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously.” That people would do work without being paid may be mystifying in an economic context of scarcity, but in a condition of abundance people become more willing to contribute to others. Open collaborative design therefore goes hand-in-hand with abundance; they feed off each other. This is shown in Maslow's pyramid below: Abraham Maslow's well-respected theory of motivation It is interesting to note that scarcity-based economies focus on man's two lowest needs: security and physiological needs, while in a situation of Post-scarcity the lower needs are a non-issue, so the higher needs come into sharper focus. It has been shown again and again and again in psychological studies that extrinsic carrot-and-stick motivation is effective only at tasks that require no insight or creativity i.e. mechanistic tasks. But our society is moving towards automating more and more of these tasks, so that the jobs left for people to do are the ones that require dealing with ambiguities, thinking laterally and finding creative, non-obvious solutions. For these tasks, only intrinsic motivation is effective, with extrinsic rewards and punishments usually leading to lower performance. This may be surprising (it certainly flies in the face of traditional notions of incentives) but it has been proven again and again [5][6][7].

With many people contributing to open design projects, as happens currently with software, a universal commons will emerge made up of vast libraries of designs for everything from components and sub-assemblies through to complete artefacts, machines and complex systems, available for anyone to download and incorporate into their own designs, or help evolve as part of a wider project.

As in software, it would be useful for components and assemblies to be as 're-usable' as possible in the sense of being able to be incorporated in many different machine designs. To aid this it should be possible to specify the vital dynamic functions of a component or assembly in the CAD software, so that it can easily be modified in shape and scale so it can be incorporated into a new design while ensuring it still works correctly. This will enable a huge reduction in duplication of effort and allow people to focus their efforts on creating new machines of increasing complexity and building on the work of others. One interesting side-effect of open collaboration is that it tends to lead to highly modular design. FireFox and Linux are examples of this. Modularity also leads to a high degree of reusability; someone designing a new piece of hardware or software can pick-and-mix parts of existing projects. This works well in software, but may have to be abstracted somewhat to work in physical systems where dimensions are obviously important to fit with other components. Perhaps not counting the scientific community, free and open-source software is where the modern concept of commons-based peer production Networks of people (both companies and individuals) collaborate via the internet to develop useful software that others can freely benefit from. Not only is the software free to use, but so is the human-readable blueprint of the software, known as the source code People who doubt the viability of the principles outlined on this page in the real world only have to look to this sector to see amazing examples of what is being achieved already.

...and there must be plenty more... Wikipedia articlesThe two articles above also list examples of existing open collaborative design projects. As this methodology becomes better known and the toolset more powerful then the projects undertaken in this manner will gradually increase in sophistication, capability and impact. Other links and articles

|

[print version]

[print version]  [update]

[update]  [site map]

[site map]Quick tour:  previous page | next page

previous page | next page

Detailed tour:  previous page | next page

previous page | next page